Next-Generation Sensory Studies Scholarship: Breaking Research

Note: This essay is excerpted from Chapter 3 of my book “Sensational Investigations: A History of the Senses in Anthropology, Psychology, and Law,” which is forthcoming from The Pennsylvania State University Press. It will be the ninth book in the “Perspectives on Sensory History” series, edited by Mark M. Smith.

David Howes

Centre for Sensory Studies

Concordia University, Montreal

Since its inception in 2006 – see “Introducing Sensory Studies” by Michael Bull et al. (2006) – sensory studies approaches to the analysis of culture and the senses have spread throughout the two founding disciplines of the field, history and anthropology. For example, as regards anthropology, there has emerged a linguistic anthropology of the senses (Majid and Levinson 2010; Majid 2021) and an archaeology of the senses (Hamilakis 2014; Skeates and Day 2020) alongside the cultural anthropology of the senses which first got things rolling. (The fourth subfield of anthropology – namely, physical anthropology, remains on the outs). Meanwhile, the cultural history of the senses has expanded exponentially: milestones include the 6 volume Cultural History of the Senses edited by Constance Classen (2014) and the “Perspectives on Sensory History” series edited by Mark M. Smith, which includes his own book, A Sensory History Manifesto (2021).

The interdisciplinary scope of sensory studies has been growing steadily, with art history (e.g. Deutsch 2021), architecture (Karmon 2021) and literary studies (Swann 2020) being among the latest fields to come on board. {Note 1}. It has also been expanding internationally. In 2016, French anthropologist Marie-Luce Gélard edited a special issue of The Senses and Society entitled “Contemporary French Sensory Ethnography”; in 2019, Mexican sociologist Olga Sabido Ramos came out with the edited collection Los sentidos del cuerpo: un giro sensorial en la investigación social y los estudios de género.

What is especially exciting to witness at the current conjuncture is how sensory studies is now going intergenerational. This development is signalled by the imminent publication of Sensibles ethnographies. Decalages sensoriels et attentionnels dans la recherche anthropologique (Calapi et al. 2022) written and edited by four recent graduates of the PhD in Anthropology programme at the Université de Nanterre.

In what follows, I would like to provide a synopsis of the work of another contingent of “next-generation” sensory studies scholars, all based (or formerly based) at the Centre for Sensory Studies at Concordia University, Montreal. The six students whose work will be reviewed here come from a range of programmes: the Ph.D. programme in Social and Cultural Analysis (SOAN), the Interdisciplinary Humanities Ph.D. programme (HUMA), the Individualized Ph.D. programme (INDI), and the Master’s programme in Social and Cultural Anthropology. In order to present them best, let me group their works under three rubrics: the more-than-human sensorium, sensory ethnography, and research-creation.

The More-Than-Human Sensorium

Mark Doerksen is a graduate of the Ph.D. program in Social and Cultural Analysis. His doctoral dissertation was entitled “How To Make Sense” (2018). In it, he reports on his field research in Canada and the United States on a subculture of the body modification movement known as “grinders.” Grinders are not satisfied with the normal allotment of senses. They implant magnets in their fingers so as to be able to sense electromagnetic fields. Doerksen followed suit so that he could sense along with them what they experience.

There is no dedicated vocabulary for electromagnetic sensation; nor are there any medically-approved procedures for fashioning an “nth sense,” as Doerksen (2017) calls it. Grinders must therefore improvise, or “hack,” as they say. They practice DIY surgery, which exposes them to many risks, as no medical professional would support or aid them in their quest.

The grinders’ reports of their experience of an otherwise insensible dimension of the material environment (e.g. the emanations of microwave ovens and electronic security perimeters) represent an intriguing opening beyond the bounds of sense, as most humans know it. Here is how one novice grinder described his experience of a trash compactor:

My favourite thing I’ve ever felt was actually during when I had my first implant. So it was still super fresh, not really sensitive, but at my old job we had this trash compactor in the back of the store, and every time I would take out the trash … just walking into the vicinity [I would get] this buzz … I like to say it feels like you’re walking toward this super powerful object, but, I mean, really you are. That is what you’re feeling because there is so much electricity going through that [machine] … as if it were some mystical artefact or something that was the energies emanating from it. I haven’t yet, but I still want to go back now that I have a fully healed [magnetic implant] on my finger just to feel what it feels like at peak sensitivity (Doerksen 2018: 136)

Grinders could be likened to the X-men of Marvel Comic fame, only instead of their supersensory powers being the result of some genetic mutation, they develop their own sensory prostheses, such as the magnetic implants, and also ingest chemicals and follow strict dietary regimens. Doerksen found that grinders tend to have a superiority complex, and are also deeply distrustful of many social institutions, especially those of the “academic-industrial complex,” yet even though he could have been seen as a representative of the latter complex, these sensory anarchists accepted Mark into their ranks and shared their (extrasensory) experiences with him.

∫∫∫

Joe Zeph Thibodeau obtained a Master’s degree in Music Technology from McGill University in 2011, and worked as a technician in the Penhume Laboratory for Motor Learning and Neural Plasticity between 2011 and 2018. He runs a typewriter rehabilitation business on the side and has long been a volunteer at the Right to Move/La voie libre, a bike repair cooperative located near the downtown campus of Concordia.

Thibodeau enrolled in the Individualized Ph.D. program in September 2018 to pursue research on sensation, perception and human-machine interaction. His research seeks to reconfigure the human/machine polarity by focussing on the multiple possible relationships between humans and machines and exploring how reframing the relationship may impact the identities of the parties to the conjuncture.

In 2019, Thibodeau staged a three-week public “research performance” called Machine Ménagerie in which he worked at developing an assortment of small autonomous robots that were “cute as heck” (see Figure 1), and engaged in a running dialogue with visitors to the installation. Due to their charm (partly a function of their size and partly of their apparent helplessness), the robots incited “affective interactions” both with each other, and with the visitors who befriended them. The latter would talk to them, separate them when they became entangled, intervene to prevent them from toppling off the display table, and even ask to take them home, so as to prolong the interaction. This contributed to the emergence of a conception of sentience as “collectively negotiated through performance” (Thibodeau and Yolgörmez n.d.: 4). It would be easy, too easy, to theorize these responses as projections of human affects, or as fetishizations of the machines. Rather, what they index is relationality, and “the proof is in the performance,” as Thibodeau puts it.

Figure 1: Joe Zeph Thibodeau. “Photo day at the original Machine Ménagerie Installation, 2019, at the “Thinking about AI” exhibition in the 4th Space gallery. Zoulandur, a sophisticated and purposeless robot, poses for the camera while the rest of their housemates loiter in the background.” Photo and text credit: Joe Zeph Thibodeau.

Figure 2: Chronogenica, 2021. “A handshake between comrades. Machines and humans can build a brighter future for themselves with new kinds of hybrid organizations.” Chronogenica, 2021. Photo and text credit: Chronogenica

The design and exhibition of Machine Ménagerie led to the publication of two papers which Thibodeau co-wrote with fellow Ph.D. student Ceyda Yolgörmez (who is enrolled in the Social and Cultural Analysis doctoral program). In their analysis, Thibodeau and Yolgörmez observe (n.d.) that the question “Can machines think?” has long dominated research in Artificial Intelligence (AI); and, as more and more thinking-machines have been created, the further question has emerged: “Given their increasingly autonomous intelligence, might machines eventually outsmart and dominate us?” In the latter view, intelligence is typically treated as a measurable quotient: a machine either has it, or does not. There is a prior question, however, the question: “Can machines feel?” but it is typically skipped over either because it is deemed less interesting, a merely technical issue, or due to the conventional valorization of intellect over affect.

Thibodeau and Yolgörmez resist the privileging of intelligence over sentience, and “the binary logic of domination” that informs “the myth of AI” (the nightmare scenario of accidentally unleashing a superintelligence). What is more, the authors advocate that the notion of sentience be approached “relationally” – that is, not as some hypostatized “agential capacity” but as embedded in the relationalities between humans and machines. This opens the way for “the cultivation of an attention towards the concrete situations and encounters where machines are treated as sentient,” or “being-together-in-the-world” with machines (Yolgörmez and Thibodeau n.d.: 1). By shifting the focus from the attribution of intelligence and agency to a non-human entity to the “affective encounters” between humans and machines, the way is also opened for entertaining other sorts of relations, such as care in place of domination, and mutuality in place of instrumentality.

For one of his comprehensive exams, Thibodeau registered a business, a machine-human cooperative, and proceeded to write a constitution for a sort of parliament, or “assembly” made up of the tools in his workshop (whom he treats as colleagues) and himself. (The model of the cooperative was inspired in part by Thibodeau’s prior experience volunteering at the RtM/Lvl co-op.) He calls this business “Chronogenica” (Thibodeau n.d.). For this parliament to be representative, Thibodeau had to share authority with the tools in his workshop, such as Verne the caliper, Savu the pliers, Aristo the typewriter, and Mole Vice the wrench (see Figure 2). This entailed a novel “(re)distribution of the sensible” and a total “(re)distribution of agency” — or rather, it involved drilling down to recognize the mutuality of the relationships tools and humans already enjoy with each other. He gauged the tools’ voices (or “will”) by being attentive to them (conversing, holding, gripping, moving, pondering, typing) with a view to arriving at a con-sensus. It is an interesting question whether the relationalities the Chronogenica constitution articulates as principles of consociation should be seen as “intersubjective” or “interobjective,” as “(still) all too human” or “posthuman”?

Sensory Ethnography

Roseline Lambert is an award-winning poet in addition to being a trained anthropologist. As such, she belongs to an anthropological tradition that includes Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead and Edward Sapir, all of whom led a double life as poets (Reichel 2021). Those anthropologists kept their poetry separate from their anthropology, though, whereas Lambert has sought to fuse the two in her ethnographic practice. She is a poet-anthropologist.

Lambert’s doctoral thesis is entitled “Le reflet du monde est à l’intérieur de moi: une ethnographie poétique de l’expérience de l’agoraphobie en Norvège” (2021). Her thesis built on the research she did for her Master’s degree at the Université de Montréal interviewing members of the (5,000 strong) francophone virtual community of agoraphobes in Quebec. She also drew on her experience of agoraphobia during her teenage years, so her research was grounded in participant sensation.

For her doctoral research, Lambert travelled to Norway, which has the highest per capita concentration of diagnosed agoraphobes in the world, and took up residence in a quarter of Oslo adjacent to the quarter where the painter Edvard Munch dwelt. Munch spent the last thirty years of his life cloistered in his studio. He was (and remains) the most famous agoraphobe of all time, and is best known for his painting “The Scream,” which is the most powerful depiction of the state of anxiety in the history of Western art.

Ever since the first diagnosis of agoraphobia in 1871, it has been seen as a spatial disorder. The 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) defines agoraphobia as: “A marked fear or anxiety about two (or more) of the following five situations: Using public transportation/Being in open spaces/Being in enclosed spaces (e.g., shops, theaters, cinemas)/Standing in line or being in a crowd/Being outside the home alone.”

Lambert sensed things differently during her sojourn in Norway. She was struck by the way Norwegians in general seemed to be preoccupied by the ambient light: they talked about light the way most other Europeans and North Americans talk about the weather. Like other Scandinavians (Bille 2013), Norwegians are renowned for abjuring fluorescent or LED lighting, and for burning candles in the middle of the day for no good reason other than it makes them/things feel “cozy” (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Candles in the sun. View from an apartment in the Grünerløkka

quarter of Oslo, Norway. Photo credit: Roseline Lambert.

Lambert found that the Norwegian agoraphobes she interviewed spend countless hours at the windows of their apartments, looking out. She accordingly devotes a section of her thesis to analyzing the material culture of the window. The social and sensory dimensions of other typically Norwegian objects, environments and representations also attracted her attention. For example, she noted, and several authors affirm, that Norway is a particularly “home-centred” society wherein the house (hjeme) is diametrically opposed to the exterior (ute) and to the social. The remote cabin (hytte) in the woods is a highly cherished location.

Lambert found that the Norwegian imaginary is populated by many revered figures (the Viking, the sailor, the soldier) who do not fear going out, which exacerbated her interlocutors’ sensitivities about their own misgivings in this respect. And, her inquiries revealed that her interlocutors were acutely conscious of their contradictory position in Norwegian society: the social democratic welfare system supports them and assures them of an income even if they cannot go outside to work; at the same time, they must constantly prove to the state, and their social network, that their disorder is a real medical condition and not some form of laziness. The fall-out from this is that agoraphobes are at high risk for being stigmatized and excluded from Norwegian society.

Lambert’s sojourn in Norway was cut short by the onslaught of the novel coronavirus pandemic in the Spring of 2020, when her family called her home. Consequently, she did not have the chance to document and poeticize the seasonal light cycle for a full 12 months (only from July 2019 to March 2020). However, she was able to continue interviewing the participants in her study by moving the interviews online. It emerged that her interlocutors, who already spend most of the time inside their homes, considered themselves to be masters of confinement with a lot to teach the rest of the world about living in isolation.

In exploring the sensory etiology of agoraphobia, Lambert has made an important contribution to sensualizing the field of medical anthropology. She has also made a signal contribution to (re)setting ethnography to poetry. Let me close by citing a sample of her poetry:

la nuit ≠ noire

sur la place de la gare centrale je flatte le tigre

je ne sais pas si le soleil se couche si je dors

mes yeux ouvrent mes yeux ferment c’est blanc

une ligne ≠ un phare

quatre feux jaunes clignotent au coin de la rue

le tramway approche

je ne sais plus dans quelle direction partir

mes lignes s’entrecroisent

∫∫∫

Erin Lynch is a practitioner of sensory anthropology in the tradition of Sarah Pink, author of Doing Sensory Ethnography(2009). Pink has contributed substantially to sensualizing the discipline by “engaging” the senses in visual anthropology (Pink 2006), digital ethnography (Pink et al. 2015), and design anthropology (Pink et al. 2016; Pink 2021). In Lynch’s research for her doctoral thesis, however, the focus is slightly different: she takes Augmented Reality (AR) as the object of her investigation. In 2015, she embarked on a multi-city odyssey which took her first to London, Edinburgh, Dublin, and Derry and then, during a second jaunt, to Seattle, Hong Kong, Melbourne, Christchurch and San Francisco, followed by side trips to New Orleans and Toronto, and then back to Montreal.

Lynch’s doctoral thesis could be classified as a contribution to the anthropology of tourism, but whereas most theorizations of tourism have focussed on “the tourist gaze” (Little 1991, Urry and Larsen 2011), she trained her senses on how smart phones equipped with locative apps mediate the experience of the urban; hence, her thesis offers a sensory ethnography of the “augmented city.”

The timing of Lynch’s research on locative tourist apps was very apt, as cities the world over scramble to brand themselves as desirable tourist destinations by offering visitors a custom-designed (and customizable) experience of the city through their smart phones. In her thesis, Lynch presents a discourse analysis of the lingo of the apps, and a visual analysis of their imagery, but she also does something more. By keeping her senses about her, she picked up on all the discrepancies between screen and world, linguistic hype and everyday soundscape. Analyzing these nonalignments between the virtual and the actual revealed as much about the design strategies and messaging of the apps as their actual content. Lynch has revised her thesis for publication as the twelfth volume in the Sensory Studies series from Routledge, and it is due out in the Fall of 2022 (Lynch 2022)

Shortly after defending her thesis, while she was a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Sensory Studies and a Research Associate on the “Explorations in Sensory Design” project, Lynch led an inquiry into the sensory ambiance of the Casino de Montréal. The results of this inquiry were subsequently published in an article in The Senses and Society entitled “A touch of luck and a ‘real taste of Vegas’: A sensory ethnography of the Montreal casino” (Lynch et al. 2020). Through employing the methodology of participant sensation, this research revealed how the ambiance of the casino is not simply dictated by the “experience design” experts hired by the casino management to create a specific atmosphere, but rather co-produced by the casino’s patrons.

“Vegas Nights” was the chosen theme at the time of the research, and the casino was accordingly replete with Elvis impersonators, sequined showgirls, and a wedding chapel where patrons could get married “for fun.” The décor was overwhelmingly visual, and the music very loud and intense, but the research also drilled down to expose how the other senses were titillated: the taste by means of overly sweet “free drinks” and the “explosion of tastes” at the in-house restaurant belonging to the Michelin-starred Atelier Jöel Robuchon chain; the touch by means of the ritual gestures at the blackjack table (with its plush felt surface) and the ergonomically-designed seats at the electronic gambling machines (EGM) that envelop the player in a world of their own. It did not appear that the Montreal casino scented the machines to induce a particular mood, unlike other casinos (Hirsch 1995), which was perhaps a missed opportunity.

“Par pur plaisir” is the inscription on the carpet at the entrance to the casino. But within its walls not everything is pleasure, or all that “fun” for that matter. (The casino bills the experience it offers as “fun for all the senses”). Gambling has become routine for many, and an addiction for others. In recognition of the latter social problem, since 2006 has contained a Centre du Hasard, or “responsible gaming station.” According to Loto Quebec’s “A Game Should Remain a Game” page (Loto-Quebec, n.d.), such information kiosks have been installed in all of Quebec’s casinos, and are designed to illuminate the nature of games of chance, heighten players’ awareness of gambling’s associated risks, and “[s]uggest strategies to lower the risk of losing control over gambling habits.” (Loto-Quebec, n.d.).

The Centre du Hasard is a so-called harm reduction measure which, as Lynch notes,“likely reflects the tenuous position of being a government-affiliated organisation peddling a (potentially) addictive product” (200). One of the displays in the station invites patrons to spin a wheel to “play the lucky number game” – the point of which is to reveal that there is no such thing as a lucky number. In another installation,

the inner workings of an old-style machine – with spinning reels and a crank lever on the side – are exposed. The purpose of this mechanical strip tease is revealed by comparison– the attendant demonstrates that, as with the older machines, the numbers on the digital slot machines are set from the moment you push the button. All of the spinning, the sound effects, the rumbling and pizazz is purely for show (200)

The clinical feel of the responsible gaming station offsets, but hardly competes with, the sensory maelstrom and electronically amplified ambiance of the other spaces in the Casino. Hence, it is a half-measure at best.

Lynch was invited by the responsible gaming research design team attached to the Casino to present her findings and recommendation. One of the suggestions she made at this meeting was to incorporate greenery (i.e., plants) so that the experience of the casino would not be so exclusively technologically driven. It remains to be seen whether such initiatives will enable gamers to “have a life” or “get a life” apart from the “second life” in which the casino ensconces them.

Research-Creation

Sheryl Boyle is a recent graduate of the research-creation stream of the Interdisciplinary Humanities Ph.D. program at Concordia. She was also an associate professor of architecture in the Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism at Carleton University, Ottawa, and served as the Director of the program throughout her studies.

Boyle’s Ph.D. thesis (2020) proposes what she calls “sensory (re)construction as a way of knowing.” Its focus is on Thornbury Castle, built by Edward Stafford, the Third Duke of Buckingham (1478-1521) between 1508 and 1521. The Duke’s household was one of the largest and wealthiest households in England at the time, and he brought together scores of live-in artisans (masons, carpenters, cooks, gardeners, etc.) over the thirteen year period.

Approaching the building as an “epistemic site” (after Rheinberger 1997), Boyle’s thesis is laid out in three layers. The first layer has to do with the setting, which she (re)constructs using “works of the pen” (historical texts, chronicles, letters, and diagrams). It is not just the physical setting that concerns her, though, but the cosmology of 16th century England, when all sorts of humoral and alchemical notions were in the air, and the air itself was of material interest. For example, the Castle was oriented to the winds so that its walls and apertures could channel the healthy air from the Northeast and dispel bad air. This was an important consideration at the time due to the prevalence of the “Sweating Sickness,” which was understood to be brought on by stagnant air.

Figure 4: Courtyard of Thornbury castle oriented to capture the healthy north-east winds. Drawing credit: Sheryl Boyle.

The second layer has to do with the objects, methods, materials and tools, such as mortar and pestle, that were used by the artisans. But Boyle’s research is not confined to reading about these items and building up a mental picture: she learned how to fashion and became quite adept at (re)making them. For example, she (re)constructed the recipe for building mortar. The term recipe is significant here, for it turns out that the process of building was conceptualized at the time as analogous to cooking. Boyle devotes a fascinating chapter to the resemblances between the ingredients and processes of making building mortar and preparing blancmange (“white-eat”) with mortar and pestle: quick lime corresponds to capon breast, water or casein corresponds to almond milk, loaf of tuff corresponds to loaf of bread (used as a setting agent), sand corresponds to sugar, and a fragrant spirit (namely, rosewater) was used in both concoctions. Mortar filled in between bricks, while blancmange was an entremets served between the dishes at a banquet (to “open” and “close” the stomach). This was all very sensual, and very alchemical (e.g. the emphasis on the qualia of whiteness).

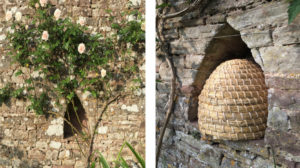

Figure 5: Roses and bee boles punctuating the walls of the privy garden at Thornbury castle. Image credits: Sheryl Boyle.

The third layer has to do with practices. One of the component parts of this layer involved Boyle (re)making four elements of Thornbury Castle in her studio: a wall, a window, a chimney, and a trestle table. (The latter was a work table and a dining table at once, and it was intended to serve as the centrepiece at the oral defense of her thesis). Each such (re)construction project involved combining different artisanal skills and creating a different, multisensory “epistemic object.” For example, her (re)construction of an oriel window involved drawing on the skills of a confectioner, gardener, and plasterer. True to the original meaning of the word window (namely, “wind eye”), Boyle constructed a panel (in place of a pane) and impregnated each of its 24 squares with the scent and flavour of flowers and honey (reflecting the fact that the façade of Thornbury Castle was dotted with boles containing beehives, and climbing plants that wafted their fragrance through the “wind eyes”). The squares of the panel were also tinctured like stained glass. Boyle’s “windows” are not for looking, they are for smelling, and imaginatively tasting: that is, they are designed to bring the environment in, rather than seal it out behind glass.

Figure 6: Verso (underside) of the drawing/table for interdisciplinary tools used by the artisan to manipulate luminosity, color, fragrance, and sweetness – four alchemical qualities. Small working areas are left in each quadrant, creating a social space for discussion and exchange, before folding along the quadrants and transported to the next site. Artwork credit: Sheryl Boyle.

A word is in order here about the requirements of the research-creation stream of the Interdisciplinary Humanities Ph.D. program. It does not suffice for a student to write a thesis. The student must also stage an exhibition, be it a performance or (as here) an installation artwork. Furthermore, the creative component cannot be a mere illustration of the thesis, nor the thesis a mere exegesis of the artwork. The two components have to speak to each other so that the resulting contribution to the advancement of knowledge is both material and intellectual, sensible and intelligible — or in short, a multimodal conversation.

Boyle’s 312-page thesis and the four (re)construction projects that accompany it constitute a brilliant, highly redolent, textural and flavourful enactment of sense-based research in architectural history. Throughout, the accent is on buildings conceived of as processes or “events” rather than such surface features as their form or style (see further Bille and Sørenson 2017). It is an exercise in the “archaeology of perception” that brings the sense(s) of the past to life.

∫∫∫

Before entering the Master’s programme in Social and Cultural Anthropology in the fall of 2020, Genevieve Collins was an active participant in the Winnipeg arts scene, working in an art gallery and making films. She was attracted to Concordia by the prospect of researching and creating an immersive sensory environment that would simulate the experience of being in outer space.

We typically think of space as vast, dark, silent, lifeless, and uninhabitable. This is because we normally view it through the lens of a telescope, or a Hollywood film. However, as recent advances in astrochemistry and acoustic astronomy have revealed, the gas clouds of the Milky Way smell like rum and, far from being a silent expanse, outer space resounds with all sorts of ringing sounds and pulsations. These are just some of the facts Collins discovered in the course of her preparatory research. The question then became: How to transduce these facts into the realm of the senses? How to create an atmosphere where there is no atmosphere (as we humans know it) to speak of?

The installation artwork Collins created, called ETHER, ran at Experisens from 3 to 8 March, 2021. {Note 2} Upon entering the tiny room where the installation was housed, my attention was drawn to three glass display cases set on pedestals wrapped in aluminum foil topped by funnels. One case contained reddish rocks and sand and when I put my face in the funnel, I breathed in a dusty and spicy scent meant to evoke the atmosphere of Mars; another case contained a cloud-like mass of cotton batting and smelled smoky and gaseous to suggest the atmosphere of Venus, with its many gassy layers; the third contained a grey-coloured plant growing out of a cushion (with an International Space Station label) that diffused a distinct organic smell (eucalyptus) along with a metallic, burnt steak smell (such as many astronauts have reported smelling upon returning from a spacewalk).

In the middle of the room there was a stand with a tray of drinks: one glass purportedly contained recycled water from Mars, slightly rusty and dusty with a hint of spice and a vaguely organic smell; another contained a frigid and refreshing distillation of the Milky Way (conveyed by means of a frozen raspberry suspended in yogourt); the third was a rocky and metallic tasting beverage dyed deep black (to suggest the darkness of outer space) that also sparkled as if the liquid were composed of the minerals extracted from an asteroid.

On opposite walls of the room there were two video projections: one was of an eye, that blinked repeatedly, as if unsure how to focus. The other projection, which ran for 20 minutes, took the viewer on a voyage around our solar system. The visuals consisted of extreme close-ups of telescopic images and microscopic images of particles (to play up the extremes of scale), as well as lightning flashes and silhouettes of the International Space Station crossing in front of the sun. The way the visuals rotated, and zoomed in and out of focus, created a vertiginous feeling in the spectator that referenced the disorienting effect of zero gravity.

The accompanying soundtrack featured oscillating and ringing sounds as well as muffled clips from the Voyager Golden Record. The blurriness of the latter sounds indexed the distortions that sonic vibrations would undergo when transduced through ice or rock or heavy gasses in addition to suggesting how an extraterrestrial being or sentient scientific device that came across the Golden Record might register it.

After my visit, I sat down with Collins to discuss my impressions. What sense had I made of all these otherworldly sensations? She recorded my reflections, along with those of all the other visitors to ETHER, and is currently analyzing them for incorporation into her Master’s thesis.

For her Ph.D., Collins proposes to make an ethnographic film and write a thesis based on fieldwork in an Arctic research station. As she writes in her proposal,

Prospective astronauts and scientists participate in long-term studies in extreme environments such as Polar research labs to simulate long duration space flight and imagine human habitation on other planets. In these training grounds or space analogues, researchers experience long term isolation, face extreme weather conditions, and study micro-organisms well adapted to the environment in order to conceive of life elsewhere in the universe. The central aims of this project are to document the sensory aesthetics of everyday life in this context, explore the dense network of subjectivities inhabiting the environment, and investigate the inherent temporal and spatial ambiguity that accompanies this scientific research. The main research questions include: How does research in space analogues engage with ideas of futurity? What are the sensory dimensions of this scientific research environment? How are human and more than human subjectivities entangled in this unique terrestrial milieu?

This proposed research points to how the anthropology of the senses – and with it the whole field of sensory studies – can move beyond traditional cultural and environmental spheres to explore new frontiers of existence and experience.

∫∫∫

In closing, the graduate student research reviewed here is manifestly stretching the bounds of sense in all sorts of sensational new directions: it is multi- and interdisciplinary, and multi- and intersensory at once. This body of research confirms that the “sensorial revolution” (Howes 2006) in the humanities and social sciences has indeed come of age (Lamrani 2021).

Notes

- The genesis (in the disciplines of history and anthropology in the early 1990s) and subsequent expansion of the (now multi- and interdisciplinary) field of sensory studies is a complex tale. There were also murmurs or intimations before the 1990s. For an account see The Sensory Studies Manifesto: Tracking the Sensorial Revolution in the Arts and Human Sciences (Howes 2022).

- Experisens is a sensory evaluation research laboratory attached to the Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec, which provided partial funding for the project. Collins hired a sound artist and a smell artist to assist her with the sonic and olfactory compositions; the drinks and visuals she mixed herself

References

Bille, M. 2013. Lighting up cosy atmospheres in Denmark. Emotion, Space and Society, 15:56-63.

Boyle, S. 2020. “Fragrant Walls and the Table of Delight: Sensory (re)construction as a way of knowing, the case of Thornbury Castle 1508-1521,” Ph.D. dissertation, Concordia University.

Bull, M., Gilroy, P., Howes, D., and Kahn, D. 2006. Introducing Sensory Studies. The Senses and Society 1(1): 5-7

Calapi, S., Korzybyska, H., Mazzella di Bosco, M. & Peraldi-Mittelette, P (eds.) 2022. « Sensibles ethnographies. Decalages sensoriels et attentionnels dans la recherche anthropologique. » Marseille: Éditions Petra.

Classen, C. (ed.) 2014. A Cultural History of the Senses, 6 vols. London: Bloomsbury

Deutsch, A. 2021. Consuming Painting: Food and the feminine in Impressionist Paris. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Doerksen, M. 2017. Electromagnetism and the Nth Sense: Augmenting senses in the grinder subculture. The Senses and Society 12(3): 344-349

Doerksen, M. 2018. “How to Make Sense: Sensory Modification in Grinder Subculture.” Ph.D. dissertation, Concordia University. Accessible at: centreforsensorystudies.org/how-to-make-sense-sensory-modification-in-grinder-subculture/

Gélard, M.-L. (ed.) 2016. Contemporary French Sensory Ethnography. Special issue, The Senses and Society 11(3)

Hamilakis, Y. 2014. Archaeology and the Senses: Human Experience, Memory and Affect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hirsch, A. R. 1995. “Effects of Ambient Odors on Slot‐machine Usage in a Las Vegas Casino.” Psychology & Marketing 12 (7): 585–594.

Howes D. 2006. Charting the Sensorial Revolution. The Senses and Society 1(1)

Howes, D. 2022. The Sensory Studies Manifesto : Tracking the Sensorial Revolution in the Arts and Human Sciences. University of Toronto Press (in press)

Karmon D. 2021. Architecture and the Senses in the Italian Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lambert, R. 2021. “Le reflet du monde est à l’intérieur de moi: une ethnographie poétique de l’expérience de l’agoraphobie en Norvège.” Ph.D. dissertation, Concordia University.

Lamrani, M. (ed.) 2021. Beyond Revolution: Reshaping nationhood through senses and affect. Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 39(2) special issue

Little, K. 1991. On safari: the visual politics of a tourist representation. In D. Howes (ed.) The Varieties of Sensory Experience. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Loto-Québec. n.d.. “Awareness Programs and Measures: Casinos and Gaming Halls.” A game should remain a game. lejeudoitresterunjeu.lotoquebec.com/en/gambling-quebec/programsand-measures

Lynch, E. (in press) Locative Tourism Apps: A Sensory Ethnography of the Augmented City. Abingdon: Routledge.

Lynch, E., Howes, D. and French, M. 2020. “A touch of luck and a ‘real taste of Vegas’: A sensory ethnography of the Montreal casino.” The Senses and Society 15(2): 192-215.

Majid A and Levinson S. (eds.) 2010. The Senses in Language and Culture. The Senses and Society 6(1) special issue.

Majid A. 2021. Human Olfaction at the Intersection of Language, Culture and Biology. Trends in Cognitive Science 25(2) www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364661320302771?dgcid=raven_sd_aip_email

Pink, S. 2006. The Future of Visual Anthropology: Engaging the Senses. London: Routledge

Pink S. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnography. London: Sage

Pink, S. et al (eds) 2015. Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. London: Sage.

Pink, S. et al (eds.) 2016. Digital Materialities: Design and Anthropology. London: Routledge.

Pink, S. 2021. Sensuous Futures. The Senses and Society 16(2)

Reichel, A.E. 2021. Writing Anthropologists, Sounding Primitives: The Poetry and Scholarship of Edward Sapir, Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Sabido Ramos, O. (ed.) 2019. Los sentidos del cuerpo: un giro sensorial en la investigación social y los estudios de género. Mexico : Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Skeates, R and Day J (eds.) 2020. The Routledge Handbook of Sensory Archaeology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Smith, M.M. 2021. A Sensory History Manifesto. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Swann, E. L. 2020. Taste and Knowledge in Early Modern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thibodeau, J. and Yolgörmez, C. 2020. Open-source Sentience: The Proof is in the Performance. Paper presented at ISEA2020. Accessible at www.isea-archives.org/isea2019/isea2020-paper_thibodeau_yolgormez/

Urry, J and Larsen J. 2011. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. London: Sage

Yolgörmez, C. and Thibodeau, J. (in press). Socially Robotic: Making Useless Machines. AI and Society