The Taste of Tongues

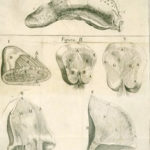

Fig. 1. Amanda Couch, “The Taste of Tongues” (Couch 2018, 256). Reproduced courtesy of the artist.

In the photography that illustrates her recipe “The Taste of Tongues,” the Surrey-based interdisciplinary artist Amanda Couch arrestingly draws the viewer’s gaze to the liminal zone that constitutes the image’s vanishing point: the very moment in which the porous surfaces of both human and ox tongue establish contact with each other, touching and licking each other, tasting each other’s flavours, and therefore blurring the boundaries between human and animal, object and subject, taste and touch (who’s touching who, who’s tasting who?) (fig. 1). Couch offers a close-up of what has long been concealed from the history for art: the open mouth, and the very act of tasting.

An imaginary diagonal line drawn from the upper left corner of the photograph slides down to the bottom right, dividing the composition of the image into two contrasting areas. This line becomes simultaneously accentuated and effaced at the previously mentioned meeting point: the sensing tongues.

On the right side of the picture, the artist presents an unconventional portrait, composed by a fragmented view of the body: a porous nose; a cross-section of a flushed and freckled left cheek; and a pink, soft, damp, and fleshy tongue sticking out of a wide-open mouth. Traditionally, a portrait would express the artist’s ability to step back and render a bigger picture of the sitter’s subjectivity. In order to do so, they would make use of a series of gestures, appearances, surfaces, and possessions, presenting a frontal view of the upper part of the body; a certain look in the eyes; a detail of the fabrics either concealing or uncovering skin (white lace, soft velvet, stained tatters); and a pair of hands either gracefully holding perfumed leather gloves, forcefully grabbing a kitchen knife, or innocently carrying a puppy. In contrast, Couch’s portrait begins right where the eye ends, and the rest of the body has to be imagined. Instead of stepping back, and offering a distant and objective view of the subject, the artist zooms in, and every detail of the lower part of the face appears so close that it is possible to discern the multiple minuscule pores that inhabit the sharp nose; the cracks and folds that wrap up the skin; and a full view of the tongue: the fibrous texture of its papillae, its wetness, its rosy tint, and its glazed look. Here, subjectivity is reversed, turned outwards, exposing the skin and a flayed interiority—a corporeal interiority that escapes through the open mouth.

A monumental greyish-brown body occupies the left side of the image. With erected pores that populate its mushroom-like surface, fatty skin flakes and cartilage, and a suspended thick drop of fluid (which suggests its living nature), the tongue of an ox stands firm on its own. Compared to the subject on the opposite side, this appendage appears significantly bigger, and entirely detached from the rest of the body: no snout, no cheeks, no mouth, and most of all no eyes: the tongue is sovereign. At its thick and cartilaginous base, which holds it tall, firm and erect, we see the tip of two human fingers, which possibly belong to the subject on the right, transgressing what would have otherwise belonged exclusively to the compositional domain of the ox. Exercising only a very gentle pressure upon its surface, this suggested touch appears closer to caressing than to violent possession. First tongue-on-tongue, and now hand-on-tongue, these two zones of contact blur the initial separating line. In an act of mutual touching and tasting, Couch’s photograph suggests communion.

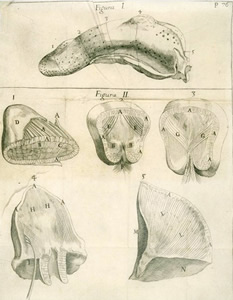

As remarked by the cultural historian Viktoria von Hoffman, the visibility of the mouth’s inner appendage had been appropriated by ‘the medical gaze,’ and rendered visible only by the monochromatic nature of ink, as in the different figures illustrating Marcello Malpighi’s anatomical examinations (Von Hoffman 2016, 101) (fig. 2). Here, the Italian physicist treats the tongue as an autonomous object of study, and shows the different views and cuts appropriate for anatomical inspection, mimicking the cuts made by his local butcher in the outskirts of Bologna. Likewise, art history had butchered and extirpated the tongue out from its official discourse. In this image, Couch cuts the stitches that had shut the mouth closed, putting it back into the body, and glueing it back to the eye, lubricating something more than the viewer’s distant gaze.

Fig. 2. Marcello Malpighi, Studio anatomico sulla struttura della lingua (1665).

References

Couch, Amanda. 2018. “The Taste of Tongues.” TASTE, edited by Andrea Pavoni, Danilo Mandic, Caterina Nirta, and Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, 245-56. London: University of Westminster Press.

Von Hoffman, Viktoria. 2016. “The Taste of the Eye and the Sight of the Tongue: the Relations between Sight and Taste in Early Modern Europe.” The Senses and Society 11(2): 83-113.

Laura Eliza Enríquez

Concordia University, Montreal, Canada