Doing Sensory Anthropology

David Howes and Constance Classen

The purpose of this chapter is to present a paradigm for sensing and making sense of other cultures. We want to emphasize the practical and open-ended nature of the discussion that follows. It sums up some of the main points of the chapters in The Varieties of Sensory Experience: A Sourcebook in the Anthropology of the Senses (hereinafter VSE) but is equally concerned to open up new directions and questions for research.

The chapter begins with a discussion of some general considerations which ought to be borne in mind when studying the sensorium. The next two parts are concerned with field research and library research respectively. They offer practical advice on, among other things, how best to clear one’s senses for purposes of sensory analysis, and how to read between the lines of an ethnography for information on a culture’s ”way of sensing” or “sensory profile.” The fourth part is called ‘A Paradigm for Sensing,’ It is divided into ten sections. The sections are entitled: 1) language, 2) artefacts and aesthetics, 3) body decoration, 4) childrearing practices, 5) alternative sensory, modes, 6) media of communication, 7) natural and built environment, 8) rituals, 9) mythology, and 10) cosmology. These headings refer to those cultural domains which, in our experience, have proved the most informative with regard to eliciting a given culture’s –sensory profile’ ‘

Some General Considerations

Other cultures do not necessarily divide the sensorium as we do. The Hausa recognize two senses (Ritchie, ch. 12 VSE); `the Javanese have five senses (seeing, hearing, talking, smelling and feeling), which do not coincide exactly with our five’ (Dundes 1980: 92). In short, there may be any number of `senses,’ including what we would classify as extrasensory perception – the `sixth sense.'(1) According to the Peruvian curer interviewed by Douglas Sharon in Wizard of the Four Rinds, for example, a sixth clairvoyant sense opens up when all five other senses have been stimulated through the use of hallucinogens and other ritual elements (1978: 117). Eduardo, the curer, describes this sixth sense as ‘a "vision" much more remote … in the sense that one can look at things that go far beyond the ordinary or that have happened in the past or can happen in the future’ (Sharon 1978: 115).

The senses interact with each other first, before they give us access to the world, hence, the first step, the indispensable starting point, is to discover what sorts of relations between the senses a culture considers proper. One commonly finds that when a particular sense is emphasized by a culture, some other sense emerges as its opposite, and becomes the target of repression. It is also quite common to find one sense substituting for another, more dangerous, sense. For example, Desana men, who manifest a high degree of anxiety regarding sexual contact, would appear to use sight as a substitute for touch when they relive birth and other sexually related experiences through the visual imagery of hallucinations (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1972, 1985a: 4). In Islamic society, the repression of sight which results from the prohibition on the visual representation of God or creation, and the fear of being accused of casting the `evil eye,’ would seem to be designed to emphasize hearing (and obeying or `submitting’ to) the word of God.

Senses which are important for practical purposes may not be important culturally or symbolically. For instance, while sight is greatly valued by the Inuit for hunting and other activities, it does not have the symbolic importance of hearing and sound, which are associated with creation. Language, in fact, is likened by the Inuit to the knife of the carver which creates form out of formlessness. Sight can thus be said to be of practical value for the Inuit because it perceives form, but sound has cultural priority because it creates form (Carpenter 1973: 33, 43). An analogous profile is presented by the Suya of Brazil who, as discussed in ch. 11 VSE, privilege speech and hearing:

In discussion of Suya ideas about vision, the ability to see must be distinguished from the symbolic meaning of the eyes. Good everyday sight, in the sense of accurate reception of visual stimuli, is apparently unrelated to the other modes [i.e., speaking and hearing] because it is not symbolically elaborated. The Suya prize a good hunter who can accurately shoot fish and game. It is not his sight that is stressed but the accuracy of his shooting. Hunting medicines are applied to the forearm to make a man a good shot, not to his eyes. (Seeger 1975: 215)

Sensory orders are not static: they develop and change over time, just as cultures do. Some of the sensory expressions of a society, manifested in its language, rituals, and myths, may be relics or survivals from an earlier sensory order. This is particularly evident in societies `with history’ (i.e. where records of earlier ways of life are extant). For example, Mackenzie Brown (1986) gives a fascinating account of how visuality came to dominate aurality in the history of the Hindu tradition, based on a reading of India’s sacred texts.2 As another example, the Latin-based word `sagacious,’ which now means only `wise,’ originally, at a more olfactory-conscious period, meant ‘keen-scented’ as well. In societies `without history’ (i.e., those for which earlier records do not exist), this kind of sensory layering is more difficult to discern, but not impossible. In Do Kamo: Person and Myth in the Melanesian World, Maurice Leenhardt (1979) was able to trace the origin of certain olfactory and visual representations of the body to different stages of Melanesian civilization by relating the representations in question to evolving concepts of space (see further Howes 1988). In such cases, the contemporary relevance of a given sensory expression can only be determined by relating it to the total sensory dynamic of the culture.

There may be different sensory orders for different groups within a society, for example, women and men, children and adults, leaders and workers, people in different professions, as will be discussed below in the section on alternative sensory modes.

Doing Field Research

If one’s research involves participant observation, then the question to be addressed is this: Which senses are emphasized and which senses are repressed, by what means and to which ends? This complex question can be broken down into a variety of subsidiary questions, which range from the particular to the general. Particular questions would include: Is there a lot of touching or very little? Is there much concern over body odours? What is the range of tastes in foods and where do the preferences tend to centre? At a more general level: Does the repression of a particular sense or sensory expression correspond to the repression of a particular group within society? Or, how does the sensory order relate to the social and symbolic order?

Every culture strikes its own balance among the senses. While some cultures tend toward an equality of the senses, most cultures manifest some bias or other, either privileging a particular sense. or some cluster of senses. In order successfully to fathom the sensory biases of another culture, it is essential for the researcher to overcome, to the extent possible, his or her own sensory biases. The first and most crucial step in this process is to discover one’s personal sensory biases.3 The second step involves training oneself to be sensitive to a multiplicity of sensory expressions. This kind of awareness can be cultivated by taking some object in one’s environment and disengaging one’s attention from the object itself so as to focus on how each of its sensory properties would impinge on one’s consciousness were they not filtered in any way (see Merleau-Ponty 1962; Rawlinson 1981). The third step involves developing the capacity to be `of two sensoria’ about things (Howes 1990c), which means being able to operate with complete awareness in two perceptual systems or sensory orders simultaneously (the sensory order of one’s own culture and that of the culture studied), and constantly comparing notes.

The procedure sketched above may be illustrated by taking the example of blood. Blood has a variety of sensory properties: it is warm, viscous, red, salty and odorous. The salience of these properties, however, depends on the sensory order within which they are perceived. Thus, North Americans tend to think of blood in terms of its visual appearance, its redness. In South India, practitioners of Siddha medicine give priority to the tactile dimension of blood; the pulse it produces within the body (Daniel, ch. 7 VSE). This holds true in Guatemala as well, although there the pulse is said to be the `voice’ of blood, suggesting an audio-tactile perceptual framework (Tedlock 1982: 53, 134). Among the Ainu of Japan, it is the odour of blood that is most salient, as the smell of blood is thought to repel spirits (Ohnuki-Tierney 1981: 97). In the myth of the Wauwalak sisters as told in northern Australia, there is reference to both the smell of blood and to ‘blood containing sound’ (Berndt 1951: 44), which implies an audio-olfactory bias.

As this brief survey illustrates, a single substance or object may figure very differently in different sensory imaginaries. But by using one’s imagination judiciously, which is to say multi-modally, it is possible to bracket or suspend one’s `natural’ way of perceiving the world, and allow these other ways of sensing, with their own biases, to inform one’s consciousness. That is the essence of `being of two sensoria’ about things. Developing such a capacity can be a source of many delights, as well as insights into how other cultures construct the world.

Doing Library Research

If one’s research is to be based on textual sources, the best method is to select an ethnography, or other piece of literature (e.g., an African novel, a life history), or even a film, and proceed as follows:

a) Extract all the references to the senses or sensory phenomena from the source in question.

b) Divide the references into intra-modal sets, and analyse the data pertaining to each modality individually after the manner of the essays by Steven Feld (ch. 6 VSE), Valentine Daniel (ch. 7 VSE), and Joel Kuipers (ch. 8 VSE) in part II of The Varieties of Sensory Experience

c) Analyse the relations between the modalities with regard to how each sense contributes to the meaning of experience in the culture, using the questions in `A Paradigm for sensing’ (see the following section) as a guide.

d) Conclude with a statement of the hierarchy or order of the senses for the Culture. Andermann’s reading of Evon Vogt’s Tortillas for the Gods (ch. 16 VSE) is exemplary in all of these respects. Note especially how the sketch of the Zinacanteco sensory order with which she concludes her piece allows for comparison with other sources on the Zinacanteco, as well as other cultures.

If one is relying on a text, there is always the problem of how the ethnographer’s own sensory biases may have influenced the selection and presentation of the material. Such biases are, at times, evident in the particular focus of the ethnography; for example, it may be a monograph on linguistics, or music, or the visual arts. At other times, one car see that the ethnographer has emphasized certain of the culture’s sensory expressions and excluded others according to the sensory model of his or her own culture. In such cases one will only be able to analyse the role of those senses which were brought out by the ethnographer. Such a problem can sometimes be resolved by examining other ethnographies on the same culture, as Pinard (ch. 15 VSE) does in his critical reading of Diana Eck’s book Darsan.

A Paradigm for Sensing

In this part, each section will begin with a series of questions which introduce the sorts of considerations one would want to bear in mind in turning to examine a given cultural domain, such as language, body decoration, or the built environment, for information on a culture’s sensory profile. The questions are followed by commentaries which elaborate on some of the ways in which the facts revealed in the course of a sensory analysis of a culture might be interpreted;.

1. Language

– What words exist for the different senses?

– Which sensory perceptions have the greatest vocabulary allotted them (sounds, colours, odours)?

– How are the senses used in metaphors and expressions?

The way the senses are used in the language of a culture can reveal a good deal about that culture’s sensory model. In the following discussion, we shall focus on the similarities and differences between Quechua, the language spoken in the central Andes, and English. (The Quechua material is derived from Gonzalez Holguin [1952] and for further background see Classen, Inca Cosmology and the Human Body.)

The level of onomatopoeia in a language may indicate the relative importance of aurality. In some cases the onomatopoeia is obvious, for example, achini in Quechua, ‘to sneeze,’ while in other cases it is more difficult to determine: Is the word otoronco, Quechua for jaguar, meant to imitate the jaguar’s roar? In any event, it appears customary in most languages for words which represent sounds to imitate those sounds, as in `crack’ or ‘thud.’ When an object or action which is multisensory, however, such as an animal, is represented by a word which mimics the sound it makes, this would seem to point to an auditory bias in that culture. Similarly, if things are usually named according to their visual appearance this indicates a visual bias, and so on. In Western languages words for objects are usually not based on any of their sensory qualities, or if they originally were, they no longer evoke these qualities for us. Perhaps this indicates a ‘de-sensualizing’ and `abstracting’ of the environment in order to render it more accessible to detached manipulation.

Some words imitate the sound supposedly produced by a certain sensation, for example, ‘ugh’ and ‘ugly.’ In many cases this may be cross-cultural. For instance, the word `aha’ is used to express a sudden experience of enlightenment in Quechua and in Western languages. Other words try to convey certain kinetic sensations, such as ‘slip.’ Visual qualities can also be indicated; for example, the word ‘glossy’ is probably meant to convey the impression of a shiny surface. In The Unity of the Senses, Lawrence Marks (1982) refers to studies which show that people associate certain vowel sounds with ‘brightness’ and others with ‘dullness.’ It is difficult to find examples of this happening with tastes or smells. Does ‘sweet’ have a sweet sound? Most examples of this kind of synaesthesia in English apparently occur with words referring to tactile sensations: `prickly,’ `smooth,’ ‘mush.’ This suggests that tactile and aural sensations have a certain closeness for English-speakers. Finally, certain sounds may be used to express value judgments. In English, for instance; many words starting with ‘sl’ have the sense of a metaphorical slippage, as in `slut’ and ‘sly’.

The importance of a sensory organ can be revealed in part by the number of words used to describe it. In Quechua there are separate terms for outer ear, inner ear, upper ear, and lower ear; outer and inner mouth and upper and inner lip; etc. The spaces between the sensory organs – that is, the space between the nose and the mouth and the space between the eyes – also have their own terms. This may simply express a preoccupation with spatial divisions; however, it likely affects the understanding of the senses as well. The concern for in-between spaces in Quechua, for example, suggests a parallel concern for how the senses relate to each other, rather than an emphasis on sensory organs as independent entities.

Terms which are used for the different senses provide the most basic source of knowledge on how the senses are understood through language. In Quechua there is a special word to indicate one who uses his senses sharply, and verbs to express the subtle use of all of the senses – ccazcachini rrtallini, `to taste subtly’; ccazcachini uyarini, ‘to near subtly’; etc. Undoubtedly, keen sensory ability is of importance in this culture. There are also words to express the loss of each of the senses through old age.

The number of terms for each of the senses is an indicator of the relative importance of that sense, or else of the different ways in which it is understood to operate. In Quechua there are verbs meaning ‘to smell any smell,’ ‘to smell a good smell,’ ‘to smell a bad smell,’ ‘to give a bad smell to others,’ ‘to smell naturally bad,’ ‘to leave a good smell,’ `to come across the remains of a smell,’ ‘to let oneself be smelled,’ etc. This implies that smell is highly important for Quechua speakers. However, the virtual absence of reference to smell in Andean myths indicates that, while smell may be important on a practical or popular level, it is less so at the level of symbols.

Metaphors for the senses provide further information on how they are perceived and valued. In Quechua these metaphors generally follow those in Western languages; for example; `to smell’ can mean ‘to discover.’ Of particular importance in this regard is to determine which sense is most associated with knowledge and understanding.

The structure of the verbs used for the different senses can also be informative. Does each sense have a separate single word? Are compound words used for some of the senses? Finally, it can be useful to look at related words. In Quechua, for instance, the verb `to see,’ ricuni, is very close to the verb ‘to go,’ riccuni. This perhaps expresses the distance involved in sight, or that seeing is a kind of vicarious going. As always, sensory metaphors must be understood within the cultural context. An association between `hearing’ and `obeying,’ for example, might indicate a positive valuation of hearing in a culture in which obedience is highly valued, but a negative valuation in one in which individual initiative is stressed.

2. Artefacts and Aesthetics

– What do a culture’s aesthetic ideals suggest about the value it attaches to the different senses?

– How are the senses represented and evoked is or by a culture’s artefacts?

– How may other senses be involv,ed in the coding, or essential to the decoding, of representations that appear primarily visual or auditory?

– What does putting a non-Western artefact ‘on display’ in a museum do to its sense(s)? How should such artefacts be presented?

In the West, aesthetic ideals are primarily visual: beauty is first and foremost beauty of appearance (Synnott 1989, 1990). In other cultures the concept of beauty may involve various senses. For the ShipiboConibo of Eastern Peru, for instance, an aesthetic experience, denoted by the term quiquin which means both ‘aesthetic’ and ‘appropriate,’ involves pleasant auditory, olfactory, or visual sensations (Gebhart-Sayer 1985).

Although all cultures would seem to have some concept of beauty, most non-Western cultures have no term for ‘art,’ nor do they privilege the attitude of detached contemplation once thought so essential to the ‘aesthetic experience’ by Western art critics. `Art’ is used rather than viewed, and the conception of beauty which goes along with this is dynamic rather than static (Witherspoon 1977). Navajo sand paintings are a case in point. Photographs of these paintings taken by tourists or art collectors capture the whole of the design from above. The Navajo. however, never see the paintings from that perspective. They situate themselves within the painting. When a sand painting is used in a healing ritual, the person to be healed, or ‘re-created’ as the Navajo say, actually sits in the painting. Sand is taken from the bodies of the holy people represented in the drawing and pressed on the body of the ill person (Gill 1987; 37-40) Thus, while outside observers see the sand paintings as visual objects; for the Navajo their tactile dimension is, in fact, more important.

The idea of sensing a painting `from within it, being surrounded by it’ (Gill 1987: 39), as the Navajo do, is foreign to conventional Western aesthetic sensibilities. Contemplation is encouraged (at the expense of participation) by rules like: `Do not touch the exhibit!’ The disengagement of all the senses, save for sight, is also encouraged by the technique of linear perspective drawing, as discussed by Howes in the Introduction to The Varieties of Sensory Experience. This technique is foreign to most non-Western cultures. Among the Tsimshian of the Northwest Coast, for example, one finds a style, known as ‘split-representation,’ that is the complete antithesis of linear perspective vision. Consider the representation of ‘bear’ taken from a Tsimshian housefront in Figure l.

If we ask `What is the point of view expressed in this representation?’ we are forced to admit that it does not have one, but many, as many as there are sides to Bear. The animal has, in fact, been cut from back to front and flattened so that we see both sides of Bear at once; as well as the back, which is indicated by the jagged outlines meant to represent its hair (Boas 1955: 225). Since we know that one cannot see an object from all sides at once, we conclude that the artist `lacked perspective.’ But what we ought to be asking ourselves, following Carpenter (1972), is how the artist’s hand might have been guided by the multidirectional ‘perspective’ of the ear rather than the unidirectional ‘perspective’ of the eye, given that his culture is an oral-aural one.

[FIGURE 1: Tsimshian representation of Bear (After Boas 1955: 225)]

In effect, the Tsimshian `wraparound’ representation of Bear corresponds to the experience of sound, which also envelops and surrounds one (Ihde 1976). The ‘ear-minded’ Tsimshian would thus seem to transpose visual imagery into auditory imagery in their visual art. To understand that art involves what Edmund Carpenter has described as `hearing with the eye’ (1972: 30).

A more explicit example of an auditory-based visual representation is found in the intricate geometric designs of the Shipibo-Conibo. These designs, which are kept by the Shipibo-Conibo in glyphic books and used extensively in the decoration of artefacts and clothes, are said to embody songs. During the healing ritual the shaman, in a hallucinogenic trance, perceives these designs floating downwards. When the designs reach the shaman’s lips he sings them into songs. On coming into contact with the patient, the songs once again turn into designs which penetrate the patient’s body and heal the illness. These design-songs also have an olfactory dimension, as their power is said to reside in their `fragrance’ (Gebhart-Sayer 1985).

Geometric designs are also used extensively by the Desana of Colombia, who, like the Shipibo-Conibo, associate them with a series of sensory manifestations. The symbolic significance of Desana baskets and mats, for instance, lies not only in the design of their weave, but also in their specific odour and texture (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1985a). It is telling of the extent to which we in the West live under the thrall of the visual that, although the multisensory nature of Desana baskets is evident, while that of the Shipibo-Conibo designs is not, most Westerners would be as unlikely to pick up on the extra-visual significance of the former as they would that of the latter.

Just as artefacts and designs can have sensory significance beyond the visual, so can music have sensory significance beyond the auditory. One example of this is the design-songs described above. Another is that of Desana instrumental music, discussed by Classen in chapter 17 VSE. Desana music interrelates all of the senses. The music of the Kogi of Colombia has a specifically tactile aspect, because, for the Kogi, sacred songs are `threads’ which tie one to benevolent forces (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1974: 298). Artefacts and aesthetic manifestations, therefore, may well evoke sensory associations or resonances far beyond those immediately apparent to the outside observer.

Mlasks provide other kinds of information about a culture’s sensory order. As Edmund Carpenter (1972: 22) notes with regard to the use of masks in West Africa: ‘West African dancers and singers close their eyes partially or wholly. The masks they wear are similarly carved. Masks with open, staring eyes are rare and usually covered by hanging hemp or fur. Sight is deliberately muted.’ By way of contrast to the downplaying of vision evidenced by West African masks, a positive emphasis on vision is manifested by the paper figures used ritually by the Otomi of Mexico. The Otomi only give eyes to those figures representing good beings, such as humans, thus according a high moral value to eyesight (Dow 1986: 103). Yet another contrast is presented by the masks which the Kalapalo of Brazil make to represent powerful spirits. Kalapalo spirit masks emphasize all of the senses: eyes are fashioned from mother-of-pearl, ears protrude, noses are long, and the tongue and breath are represented by a pair of red cotton strings hanging from the mouth. This is because powerful spirits are said to be ‘hyperanimate,’ and thus possess extraordinary sensory powers. The particular auditory bias of the Kalapalo is evidenced, however, in the fact that the most important distinguishing characteristic of powerful spirits is their ability to create music (Basso 1985: 70, 245-7).

Given all that has just been said, it should be apparent that when artefacts are put on display in museums they are stripped of much of their sense. Can their sense be preserved rather than reified in museum exhibits? If so, how? Would it help to affix a note explaining the other sensory dimensions of the artefact? Or, should curators stop at nothing less than re-creating the total sensory environment in which the artefact was originally used? What might be the drawbacks of providing simulations of the latter sort (see Baudrillard 1983; Ames 1985: 10)? The problem raised here can be focused by setting oneself the task of designing an exhibit for a Kaluli drum, bearing in mind everything noted by Steven Feld in chapter 6 VSE.

The preceding discussion is somewhat one-sided, insofar as it has concentrated on how non-Western artefacts are perceived by Western observers. In the interest of balance, one should also examine how Western artefacts are perceived according to the sensory models of other cultures. In A Musical View of the Universe, for instance, Ellen Basso relates that her glasses were understood by a member of the ‘ear-minded’ Kalapalo, not in terms of their visual function, but in terms of the sound they made on being put on: ‘nngnruk’ (1983: 64).

3. Body Decoration

– What can the ways in which a culture decorates and deforms (reforms,) the human body tell us about that culture’s sensory order?

– Are any of the sense organs physically emphasized through the use of earrings, nose-rings, scarification, paint, etc.?

– Which senses figure foremost in cultural ideals of personal beauty?

The topic of body decoration is closely related to the previous section on artefacts and aesthetics. A culture’s ideals of personal beauty are influenced by its aesthetic ideals, and the ways in which bodies are decorated are often similar to the ways in which artefacts are decorated. The designs which the Shipibo-Conibo use to decorate artefacts and clothes, for instance, are also painted on the faces of members of the tribe for healing and festive purposes (Gebhart-Sayer 1983).

Body decorations (ornaments, scars) can seem purely `cosmetic,’ but they frequently convey information about group identity and social status as well. At a deeper level, they may serve to ‘embody’ a particular sensory order, as Seeger (1973) found among the Suya of Brazil. As will be recalled from the discussion in chapter 11 VSE, among the Suva ear-discs serve to emphasize the cultural importance of hearing and moral behaviour while lip-discs are associated with speaking, singing and aggression.

An interesting variation on the Suya example is presented by the Dogon of Mali. Among the Dogon, a girl’s ‘education in speaking’ begins at age three with the piercing of a hole and the insertion of a metal ring in her lower lip. This is followed by the piercing of her ears at age six. If she continues to make grammatical errors or utter uncouth remarks by age twelve, then rings are inserted in the septum and wings of her nose (Calame-Griaule 1986: 308-10). For those who come from cultures which do not postulate any connection between the organ of smell and that of speech, this practice will be found difficult to comprehend. For the Dogon, however, `Despite its invisible nature, [speech] has material properties that are more than just sound … [it] has an "odour"’; sound and odour having vibration as their common origin. are so near to one another that the Dogon speak of "hearing a smell" ‘ (Calame-Griaule 1986: 39 and 48, n. 69). Thus, according to Dogon conceptions, words may be classified by smell. Good words smell `sweet,’ and bad words smell `rotten,’ which explains the practice of operating on the nose so as to encourage the reception and utterance of ‘good-smelling words’ and the repression or deflection of bad ones. We may conclude that the Dogon (unlike the Suya) regard smell, speech, and hearing as equally `social faculties.’ At least ideally: `the mouth too ready to speak is likened to the rectum’ (Calame-Griaule 1986: 320). In other words, bad or impetuous speech is synonymous with flatulence.

Sometimes it may take some probing to discover the deeper sense of what are ostensibly `beauty marks.’ To take an example from Western culture, the artificial beauty spots which were so popular in Enlightenment France, and which we think of as purely visual, were in fact always dipped in perfume giving them an olfactory dimension (Genders 1972: 129). In modern Africa, the Tiv of Nigeria have a special marking called `catfish’ `which is incised on a young woman’s belly. When confronted with the suggestion that the designs were not purely decorative, but rather symbolic of the girls’ biological roles as wives and mothers (i.e., their fertility), the Tiv more or less agreed: `They said that the scars are tender for some years after they are made and these artificial erogenous zones make women sexier and hence more fertile’ (Brain 1979: 78). Note how the Tiv give a tactile meaning to the visual marks. What we would also note is that the heightened cutaneous awareness such markings make possible is consistent with other facts about Tiv society. Kinaesthetic awareness also appears to have been developed to a remarkably high degree in this culture: `Those of us brought up in the northern European tradition are underdeveloped rhythmically. We have a single beat that we dance to, whereas the Tiv … have four drums, one for each part of the body. Each drummer beats out a different rhythm; talented dancers move to all four’ (Hall 1977: 77-8). Is the Tiv case unique, or are scarification and related forms of body decoration normally found in those cultures which place a premium on `bodily intelligence’?

4. Child-rearing Practices

– Which of the senses do caretakers stress or repress the most in raising children? Touch, taste, hearing?

– Do the socialization practices emphasize self-control or self-indulgence, individuality or conformity?

– Are these emphases reversed or altered at any stage of a child’s development?

– Is the primary means of education visual, oral, kinaesthetic? How are children taught to conform to their culture’s sensory order?

The first moments and months of a child’s existence are of paramount importance with respect to shaping the sensory orientation that individual will manifest for the rest of his or her life. In North American society, it is customary for the newborn to be separated from its mother, swaddled, and put to sleep in a crib. In other cultures, infants are virtually always in contact with the skin of some caretaker or other. The communication styles of adults have been shown to reflect these early childhood experiences (Montagu 1978). For example, North American society is an extreme example of a ‘non-contact culture,’ in that there is considerably less sensory involvement, eye contact, and touching, and relatively greater interpersonal distance, during social interaction, than in, for example, most African societies, where child-rearing practices tend to be more tactile.

Socialization practices have also been found to influence ‘perceptual style’ (Wober, ch. 2 VSE). For example, the Inuit perform better on Witkin’s Embedded Figure tests, and thus manifest greater `field independence,’ than the Temne of Sierra Leone. Temne child-rearing practices tend to be strict, and emphasize conformity; those of the Inuit are more lenient and foster individuality. The greater ability on the part of Inuit subjects to disembed figures from surrounding fields (i.e., to experience items as separate from context) may thus be related to the greater likelihood for a sense of separate identity to emerge in Inuit society than in Temne society (Berry 1966).

Of course, the Embedded Figure test only pertains to differentiation in the visual field. As far as the Temne are concerned, it may simply be that vision is not a field of `productive specialization’ (in Ong and Wober’s sense) for them, because they attach more importance to discrimination in the auditory or proprioceptive field. This possibility must always be borne in mind. It is best gauged by examining the full range of educational practices in place in the society, as well as the amount of time allotted to each of them. Thus, in some cultures children are taught how to dance from an early age, in others to recite sacred texts from memory.5 Or again, in some cultures children (and adults) are told what to do, in others they are shown what to do. Thomas Gregor writes of the Mehinaku of the Brazilian Amazon: `The villagers are given to the use of visual aids in teaching. Whenever I failed to follow, an explanation of a ritual or custom, I was urged to wait until I could see it; then I would understand. The Mehinaku teach physical skills … by having the pupil look on as the work is performed. There are … occasional verbal explanations but these are a relatively small part of the teaching process’ (1977: 40). Different techniques may be used according to the nature of the material which is being communicated. Among the Yanomama of the Brazilian Amazon, for example, shamanistic knowledge can only be communicated in the darkness, thus a shaman speaks only at night (Biocca 1970: 72).

Children do not always manifest the same sensory order as adults. For example, it has often been observed that North American children have a greater interest in odours and tastes than do North American adults (Porteus 1990: 145-73). Among the Inuit, the self-control manifested by adults contrasts with the self-indulgence of infants. Inuit children are characterized by their `touchability.’ They are ‘cuddled, cooed at, talked to and played with endlessly’ (Briggs 1970: 71). When they cry they are instantly comforted, either through touch or through food. Indeed, nearly all delicacies are saved to be given to children for this purpose. Touch and taste, therefore, are given free rein in infancy.

As an Inuit child passes infancy, she or he is expected to learn to suppress the senses of taste and touch. Jean Briggs notes several examples of this among the Utku. When a new child is born, its older sibling is discouraged from breastfeeding by the mother as follows: `Your little sister has nursed and gotten the breast and the inside of the parka all shitty and stinky; it smells [and tastes, one word has both meanings] horrible’ (Briggs 1970: 158). Similarly, being poked in various parts of the body is a favourite game with infants. Older children, however, are warned: `Watch out, your uncle’s going to poke you if you don’t cover up and get dressed!’ (Briggs 1970: 149). Thus, older children are taught to regard as unpleasant sensations which they formerly regarded as highly pleasurable. Touch, in particular, is greatly restricted after the period of infancy. Briggs writes: `Utku husbands and their wives, children older than five or six and their parents, never embrace or kiss … and rarely touch one another in any way, except insofar as they lie under the same quilts at night’ (1970: 117).

Among the Utku, the senses which are developed in adults are sight, so necessary, for hunting and other practical endeavours, and above all hearing, by which oral traditions are passed on (Carpenter 1973: 26, 33). People in Inuit society are therefore trained to grow out of the `infantile’ senses of touch and taste into the `practical’ sense of sight and the `social’ sense of hearing. Many cultures mark such an entrance into the adult sensory and social order by a specific rite, as in the case of the Barasana male puberty rite described in the section on cosmology (see below).

272

5. Alternative Sensory Modes

– What exceptions to the dominant sensory model exist within a society?

– Are different ways of sensing attributed to or manifested by women or men?

– How are persons with sensory handicaps treated?

In the previous section we saw that children sometimes manifest a markedly different sensory order than adults. Women also frequently manifest a sensory order which differs from the dominant one. Women and men are commonly held to perceive the world in different ways, with the male way usually being normative and the female way a complementary adjunct at best, and an aberration at worst. Different sensory characteristics are often attributed to men and women as well. Among the Hua of Papua New Guinea, for instance, the inside of the male body is considered to be white, hard, and odourless, that of the female body to be dark, juicy, and fetid (Meigs 1984: 127). In the Amazon, men are commonly thought to be cold and women to be hot (e.g., S. Hugh-,Zones 1979: 111), while the reverse holds true for the indigenous cultures of Mexico (e.g., Lopez Austin 1988: 53). All of these characteristics, of course, are associated with fundamental cultural values.

Those rites which initiate a girl or boy into the adult world often serve as initiations into a particular, gender-determined sensory order. The Yanoama, for instance, believe that a woman should not speak with a louder voice than a man’s, i.e., that she should not assert herself (Biocca 1970: 136). During the female puberty rite, consequently, a girl will be shut in a cage and not allowed to speak for three weeks. After this time, she may begin to speak, but only very softly. At the moment of reemergence, her lips and ears are pierced (Biocca 1970: 82), which undoubtedly serves to mark the socialization of her speech and hearing according to the ‘correct’ female sensory order.

Aside from, but related to, these sensory differences arbitrarily imposed upon the sexes by culture, are the differences in sensory orders which women and men may actually (as opposed to theoretically) manifest. Among the Desana, for instance, the male sensory order is characterized by an emphasis on transcendent sight acquired through narcotic visions. Women, who are not allowed to take narcotics, appear to have a sensory order which emphasizes senses other than sight–in particular, touch (Classen, ch. 17VSE ).

Such sensory distinctions are invariably related to the social distinctions made by a culture between different group, as well as to the different practices of such groups. Some of the groups within society which may manifest alternative sensory modes include: religious specialists, outcasts, and, in larger societies, the ruling and working classes and ethnic groups. Among the ancient Nahuas of Mexico, for example, nobles had `the right to eat human flesh, to drink pulque and cacao, to smell fragrant flowers, and to be given the gift of aromatic burning incense’ (Lopez Austin 1988: 393).

The reactions displayed by a culture to the real or imagined sensory differences of persons from other cultures can also prove revealing of local sensory preferences. The Sharanahua of Peru, for example, see westernized Peruvians as `speakers of another language, eaters of disgusting animals like cows, potential cannibals with enormous sexual appetites’ (Siskind 1973: 49). Anthony Seeger reports that the Suya regarded his practice of taking notes as evidence that his ears were ‘swollen;’ for the Suya believe that knowledge is acquired and retained by the ear, not the eye (Seeger 1987: 11).

The treatment a culture accords to persons with sensory handicaps, notably the blind and the deaf, is especially revealing. While one must keep in mind that blindness is a handicap even in the most auditory of societies (because of the practical value of sight), it may be much less of a handicap in some cultures than in others. In certain cultures blind persons may be thought to compensate for their sightlessness by being clairvoyant, or by having supernatural powers of hearing (Paulson 1987: 5–6). Indeed, the different modes of perceiving of persons with sensory handicaps can in themselves form the basis of a fascinating study (see Sacks 1985 and 1989).

Finally, alternative sensory modes often come into play when people are rebelling against some aspect of their existence. Among the Inuit, for example, who regard excessive emotions of all kinds as dangerous, anger is usually expressed by withdrawal and rejection of all sensory stimuli. Jean Briggs gives an example of this among the Utku Inuit of the Northwest Territories: `In such moods [of anger] Raigili might stand for an hour or more facing the wall, her arms withdrawn from her sleeves the latter pose a characteristic Utku expression of hunger, cold, fatigue, and grief. If her mother tried to tempt her with a piece of jammy bannock [cake] she dropped it or ignored it. If her father tried to move her she was limp in his hands’ (Briggs 1970: 137). Another example of this rejection of external stimuli is the case of an adolescent girl in the same community who, intensely unhappy, pretended to be deaf for a summer (Briggs 1970: 137). Such withdrawal can also take the form of sleep. Sleeping long hours is a characteristic sign among the Inuit of an emotional disturbance (Briggs 1970: 281). Varieties of sensory experience thus exist not only among cultures. but also within cultures.

6. Media of Communication

– What media does a society use for communication? Is the dominant medium the spoken word, the written word, the printed word, or the electronic bit? What other kinds of sensory codes are employed?

– How do member–s of the culture react when exposed to new communications media?

– If the culture manifests a preference for ,some media of communication over others, which senses are engaged the most and how?

It is important to analyse the full range of media used for communication in the culture – music, dance, food, perfumes, designs, writing, television, etc. – and not simply those which have to do with the transmission of ‘the Word.’6 The so-called ‘orality/literacy divide’ has been shown to be misleading. As the essays in The Varieties of Sensory Experience attest, oral cultures can be quite diverse in their sensory and symbolic systems, as can literate cultures. Furthermore, not all cultures which possess writing are literate to the same degree or in the same ways (Scribner and Cole 1981). Among the Hanunoo of the Philippines, for instance, writing is used almost exclusively for romantic purposes (Frake 1983: 340). In general, one may expect a culture which is predominantly oral to manifest an auditory bias and one which is predominantly literate to manifest a visual bias. However, this is at best a preliminary typology which must be supplemented by the study of the full range of media used in a society and how they interact with one another.?

Reactions upon first exposure to Western communications media can serve as a litmus test of a culture’s sensory order. Thus, a Tully River Aborigine, seeing whites communicate with each other by means of a letter (i.e, written marks on paper), put a letter to his ear to ‘see if he could understand anything by that method’ (Chamberlain 1905: 126). As one would expect, in the local language, ‘to understand’ is expressed by the same verb as `to hear.’ Such reactions can also shed light on our own sensory order. For example, the naivety of the Western belief in the `truth of photography’ is nicely brought out in the story of the Tanzinian chief who, when shown various photos, `recognized some of the pictures of animals … but invariably looked at the back of the paper to see what was there, and remarked that he did not consider them finished since they did not give the likeness of the other side of the animal’ (Wober 1975: 80). This clash of expectations is instructive: the chief expected the picture to show what he knew about the animal in question (namely, that it has more than one side), whereas Westerners are satisfied with being shown only what one can see.

Such inventions as the telephone and television might seem to have extended the scope of human communication to an unprecedented degree, but it is important to recognize how they also limit human communication by occluding certain channels of sensory awareness – most notably smell and taste and touch. Cultures which do without these particular means of communication exploit other media – that is, they extend their senses in other ratios, which may be equally complex. Odour communication is very important to the Desana, for instance, who admire and elaborate on the use of odours by animals (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1985b). The Murngin of northern Australia have evolved an intriguing ‘audio-olfactory’ technique for communicating with whales. As one informant told Warner: `we can take sweat from under our arms and put our hands in the water, and we can put that water in our mouths and sing out the power names of that whale. It is just the same as if we were asking him for something’ (1958: 354-7). In a related form of communication found among a neighbouring people, the members of one moiety rub the sweat from their armpits on the eyes of the other moiety to enable the latter to ‘see with sacredness’ (Berndt 1951: 44). This form of communication could be considered either a form of haptic visuality or, in the alternative, olfacto-visual.

As these examples suggest, there exist many possible ways of combining the senses for purposes of communication, and the audio-visual is but one among them. The extent to which this particular combination (the audio-visual) has been developed in the West reflects the depth of our commitment to a particular ‘regime of sensory values’ (Corbin 1986), one which, significantly, privileges the distance senses. The Murngin and their neighbours have experimented with other ratios, the audio-olfactory and the olfacto-visual, and they evidently enjoy a very different mode of relating self to self, and self to world, in consequence.

7. Natural and Built Environment

– Does the natural environment call for the exercise of some senses more than others, and if so in what ways?

– How does the layout of the community influence sensory perception? Is the home sealed off from the outside world or is there an interchange of sensory perceptions?

– Does the home consist of–only one room or are there separate rooms for different activities? Does the family sleep together or separately?

Perception, like cognition, must be studied in its ‘natural setting’ (Berry et al. 1988). Perceptual experiments carried out in psychology laboratories yield clear results. Try carrying out the .same experiment in the midst of a Moroccan bazaar, the Arctic tundra, the Sepik River region of Papua New Guinea and, suffice it to say, the results will not be the same. The point here is that the natural environment does influence perception. It may call for the use of some senses more than others, or in any event in different ways from our own, as Gilbert Lewis found in the course of his fieldwork among the Gnau of Papua New Guinea:

Although it is usually easy to walk through the forest. there are no perspectives, no open views … The light is dimmed and greenish. Occasionally one passes through a path of unmoving air faintly scented by some plant like honey-suckle; one passes transient smells, of humus, of moist rotting wood or bruised fruits. The Gnau people are alert to smell … in some cases they use scent to decide the identification of trees or shrubs, scraping or cutting the bark … The canopy and confusion of trees alters sounds and calls, limiting and muffling them, but as though enclosed in a leafy hall; the sharp screech or squawks from a nearby bird sound echoes in one’s ears. I found the localization of forest sounds difficult, … although the native people were accurate in pointing to the direction and finding them. They excel in identifying bird calls. (Lewis 1976: 46)

Lewis’s account of how the environment affects the senses agrees in an interesting way with the privileging of the auditors and olfactory, modalities in the context of ritual communication, and as metaphors for cognition, in other New Guinea societies (see Howes ch. 11 VSE).9 However. as Classen points out in chapter 17 VE, cultures may seek to compensate for the restrictions imposed upon the senses by the environment. A society in which the availability of odours and flavours is limited by nature, for example, may value these all the more because of their scarcity. Witness the high value accorded to Eastern spices in the Europe of the Middle Ages (Clair 1961: 15). Therefore, contrary to Berry (1966; 1975), we would hold that there is no one-to-one correspondence between the characteristics of a culture’s physical environment (e.g., arctic tundra vs. tropical forest) and its cognitive style (e.g., field-independent vs. field-dependent).

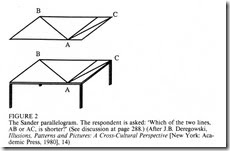

The built environment also influences perception. In a classic study. Segal et al. (1966) demonstrated that the fact of living in a `’arpentered world’ as opposed to a `circular world’ (like that of the Zulu of South Africa, with their oval huts and compounds) makes a person more susceptible to the Sander Parallelogram illusion (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

[FIGURE 2: The Sander parallelogram.(After J.B. Deregowski, Illusions, Patterns and Pictures: A Cross-Cultural Perspective [New York: Academic Press, 1980: 14) In experiments involving the Sander parallelogram (see above,), the respondent is asked: `Which of the two lines., AB or AC is shorter?’ Respondents raised in a carpentered environment usually say ‘AC’ even though AC is, in fact. 15 per cent longer than AB. Respondents raised in a circular environment. like that of the Zulu, do not usually make this error. The reason for this misperception may have to do with the Western subject automatically interpreting the two-dimensional representation as if it were three-dimensional (i.e., as if it were drawn on the surface of a rectangular table).

The built environment can also be analysed as a projection of a given culture’s sensory profile. We think of Michel Foucault’s (1979) insightful analysis of how Bentham’s design for a prison, the Panopticon, has been generalized to encompass other spaces (the hospital, the school), such that we moderns live in a `society of surveillance.’ By contrast, for the Suya, `the sonic transparency of their community makes of their village a concert hall’ (Seeger 1987: xiv). For the Inuit, `visually and acoustically the igloo is "open," a labyrinth alive with the movements of crowded people’ (Carpenter 1973: 25).

The construction of the built environment in the image of a culture’s sensory profile is apparent in the nineteenth-century English and French bourgeois fetish for balconies: `From the balcony, one could gaze, but not be touched’ (Stallybrass and White 1986: 132). It is also apparent in the proliferation of rooms within the bourgeois dwelling. This multiplication had the effect of privatizing what were once more social functions (the preparation and consumption of food, the elimination of bodily wastes, sleeping) by confining each to a separate room (Corbin 1986; Howes 1989). The fragmented (as opposed to synaesthetic) understanding of the sensorium with which we moderns operate is at least partly attributable to this great nineteenth-century repartition of space and bodily functions. Imagine the intermingling of sensations that would result fromn simply removing some of the inner walls we have built up.

8. Rituals

– In ritual settings, is any sense usually more engaged than others, for example, sight by costumes and dance, hearing by speeches and music?

– Are any senses suppressed in order to privilege other senses?

– Is there a sequence to how the senses are engaged or alternately extinguished in a ritual?

– Is the ritual specialist distinguished by the use of any one sense or particular combination of senses?

It has frequently been noted that ritual communication takes place through physical demonstration: ‘it concretely enacts assertions rather than simply referring to them in discourse’ (Knauft 1985: 247). Many anthropologists have also drawn attention to the ‘multi-channel character’ of ritual communication (Leach 1976– Stone 1986). As Fredrik Barth (1975: 223) observes of ritual performance among the Baktaman of Papua New Guinea: `Different aspects of a ritual performance reach the participant by way of each of his different senses; and the diversity of meaningful features and idioms is very great.’

Ideally, the ethnographer wants to attend to each and every message in each and every channel: for example, among the Baktaman, the smell of burning marsupial, the redness of the dancers, the different drum rhythms each invoking a different spirit, all contribute to the total meaning of the event. Regrettably, it is rarely possible for the ethnographer to attend to all these sensations at once. However, cultures also tend to be selective regarding the media they emphasize. The Suya, for instance, perform their major rituals at night, therebyexcluding the significant participation of vision and giving prominence to their ceremonial singing (Seeger 1981: 87). The Bosotho of southern Africa resort to ‘played aurality’ (as a matter of conscious preference to other sensory modes) to resolve situations of crisis (Adams 1986). The Moroccan ritual of silent wishes described by Griffin (ch. 14, VSE), where even speech is proscribed and everything centres around the burning of the seven kinds of incense, is a further example of a ritual which augments some meanings at the expense of others by restricting the number of sensory channels in use.

In addition to rituals which stimulate all the channels of sensory awareness at once,10 and those which restrict them to a few, there are rituals that accentuate and suppress different modalities according to a certain sequence. We think of the Japanese midday tea ceremony (shogo chaji), a minutely prescribed rite, which takes from three to five hours to complete. In the tea ceremony, the `progressive induction into ritual time is reflected in an increasing emphasis on non-verbal modes of communication’ (Kondo 1983: 297). Thus, conversation is permitted upon first entering the tea garden, but in the tea hut itself it is the burning incense, scrolls, and flower arrangements that set the tone. The moment of greatest symbolic intensity – imbibing the tea – is surrounded by silence. The whole purpose of this ritual is to instill a mental attitude of introspective `emptiness’ (Kondo 1983: 301); hence the sequencing of the sensations. In Japan to be introspective (which is the Zen state) is to close one’s ears but keep one’s other senses open. We close our eyes.

At the opposite extreme from the Japanese tea ceremony. which celebrates the senses in a determinate order, are those rituals designed to ‘overcome’ or ‘vanquish’ them, and thus pave the way for a transcendental experience. Valentine Daniel describes one such rite in Fluid Signs (1984). The ritual involved an arduous six-mile pilgrimage in honour of Lord Ayyappan (that was supposed to help the devotee achieve union with the deity). Daniel undertook this pilgrimage with some Tamil friends. There is a definite sequence to the order in which the senses are `merged’ or `collapsed’ in the course of this ritual. As Daniel recounts, first hearing goes, then smell, then sight, then `the sense organ the mouth’ (taste and possibly speech), and finally, all these organs having `merged’ into the sense of touch (which itself feels nothing besides pain as of this late point), that sense too `disappears,’ along with any sense of self (Daniel 1984: 270-76).11 This sequence may be read as an expression of the sensory profile of the Tamil culture of South India, hearing and touch being at opposite ends of the Tamil sensorium, the other senses in between.

The rituals described above can be said to use techniques of `sensory deprivation,’ to achieve their effects. As the sensory deprivation literature attests, restricting sensation in one channel enhances sensitivity in other channels as the sensorium seeks to recover `sensoristasis’ — that is, to compensate for the deficit (Zubek 1969). When all the senses are occluded, experimental subjects have been known to hallucinate sensations, or produce percepts from within, so as to fill the void. There is a further body of literature, less well known than the above, which concerns how applying a stimulus to one sensory channel can enhance perception in some other. For example, exposing subjects to the scent of cassia or vanillin facilitates the perception of the colour green while at the same time inhibiting the perception of red or violet (Allan 1971).

It would be interesting to analyse accounts of vision quests, shamanic flight, possession dances, and the like in the light of this literature on the application of sensory restriction and cross-modal enhancement techniques to human subjects. Lisa Andermann’s analysis of how the senses are combined in Ndembu rituals of divination (ch. 16 VSE) is a step in this direction. Another account is provided by Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatof, who describes the ways in which the Tukano restrict and stimulate the senses in order to have bright and pleasant narcotic visions:

In the first place, the participants should have observed sexual abstinence for several days before the event and should have consumed only a very light diet, devoid of peppers and other condiments. In the second place, physical exercise and profuse perspiration are thought to be necessary for the visionary experience … Next, the amount and quality of light are said to influence the sensitiveness of the participants who occasionally should stare for a while into the red glow of the torch … Finally, acoustical stimulations are said to be of importance. The sudden sound of the seed rattles, the shrill notes of a flute, or the long-drawn wails of the clay trumpets are said to release or to modify the luminous images. (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1978a: ll)

Lastly, the sensory specializations of a culture’s ritual experts can indicate which senses are considered most important by that culture. In chapter 17 VSE, Classen explores this topic in relation to the ritual experts of the Andes, who are characterized by their orality, and those of the Desana, who are characterized by their penetrating gaze. By contrast, the healers of the olfactory-conscious Warao of Venezuela must possess an acute sense of smell, as both diseases and the medicinal herbs which cure them are distinguished by their odours (Wlbert 1987). 111 cases where shamans or sorcerers are believed to stand outside society, their particular sensory characteristics can be considered to contradict the normative sensory model, as among the Suya of Brazil and the Wolof of Senegal (Howes, ch. 11 VSE).

9. Mythology

– How is the world created? By sound, light, touch?

– What kinds of sensory descriptions are contained in the myths? Is there much visual description, interaction involving touch, dialogue? How are the senses of the first human beings portrayed? If there is a ‘fall from grace,’ does this come about through the misuse of" any particular sense?

– Does a culture hero hare acute eyesight, a keen sense of smell, superior, strength, or, any particular physical characteristics?

– How, are myths passed on? Are they, told or acted?

The ‘sensory codes’ of diverse South American Indian myths have been analysed by Lévi-Strauss, and he has shown how the contrasts in one sensory modality can be transposed into those of another, after the manner of a fugue. What this form of analysis unfortunately leaves out is the whole question of the value attached to the different modalities in different societies; if factored in, these values might explain why, for example, in one of the myths discussed by Lévi-Strauss, the Opaye myth of `how men lost their immortality,’ death came because they smelled its stench, while in a Shipaya myth it came because people) failed to detect its odour (see Lévi-Strauss 1969: 147-63).

A sensorial (as opposed to structural) anthropological analysis of myth would be attentive not only to how a culture `thinks with’ smells and tastes, and textures and sounds or colours, but also `thinks in’ or ‘through’ such media (see Jackson 1989: 137-55). Since Plato, as Synnott shows in ch. 5 VSE, but particularly since the `Enlightenment’ (Ong 1967: 63, 221), the idiom of Western thought has been ocular.12 It is hard for us to imagine the world in any other light..13

The Hopi do, however. The Hopi think `in sound,’ as Kathleen Buddle has shown in a recent article called `Sound Vibrations’ (1990), which analyses the Hopi Myth of Creation. In the myth, Spider Woman brings the Twins into being by chanting the Song of Creation over them, and then commands one of them to: `Go about all the world and send out sound so that it may be heard throughout all the land.’ The Twin goes out, and: `All the vibratory centres along the earth’s axis from pole to pole resounded his call; the whole earth trembled; the universe quivered in tune. Thus he made the whole world an instrument of sound’ (Waters quoted in Buddle 1990: 10). It is consistent with Buddle’s analysis that there are no `things’ – no tables or chairs, to use the standard example of Western philosophers – in the Hopi universe, only vibrations; hence the fact that in the Hopi language one speaks of ‘tabling,’ not `a table,’ and `chairing,’ not `a chair’ (see further Whorf 1956).

In the Hopi cosmogony the world is created by sound, whereas in the Desana cosmogony the world is created by the light of the sun. The emphasis on light in the latter myth agrees with the great importance the Desana accord to sight. However, in the Desana case, the sense which is most emphasized in creation is not the one most valued in society. Sight is the subject of immense symbolic elaboration in Desana culture, because of its prominent role in creation and perception, but hearing is ultimately of greater importance because of its association with comprehension (as shown by Classen, ch. 17 VSE).14 Thus, the study of cosmogonies can provide a basis for a fuller, more nuanced understanding of the meaning of the senses in society.

Other kinds of myths can be read for information on a culture’s sensory priorities in other ways. In many myths from the Massim region of Papua New Guinea, the ancestors of humanity lack mouths or digestive tracts. Food is simply dropped in a hole on top of the head and comes out of the anus still whole. These ancestral beings only become human when their mouths (and genital orifices) are cut or burst open, which normally occurs at the same time they acquire `culture’ or rules. Thus, according to Melanesian notions, the sensory order and the social order emerged together, and `orality’ is equally central to both. Put simply, `to have a mouth’ is to be `civilized the Melanesian way’ (Kahn 1986: 171-3). As Melanesian ethnographer Michael Young observes: `The mouth, from which issues the magic which controls the world and into which goes the food which the world is manipulated to produce, is the principal organ of man’s social being, the supremely instrumental orifice and channel for the communication codes of language and food’ (1983: 172).

A culture’s ideal sensory model can sometimes be inferred from the sensory abilities and qualities manifested by its culture heroes. In a Desana myth, for instance, Megadiame, an ant-man, is presented as eating only pure foods, having perfect face paintings, giving off the odour of herbs that induce respect and love, making clear sounds while bathing, and singing and dancing well (Reichel-Dollnatoff 1971: 267). In the myths of other cultures, a hero may display one or two outstanding sensory qualities, such as a beautiful appearance, clever speech, or remarkable sexual powers. In the case of a hero who is quick-witted, but has no particular sensory characteristics, one is led to wonder whether this may not be indicative of a certain ‘desensualization’ in the culture concerned. It is not only the direct employment of the senses and sensory stimuli in myths which should be attended to, but also their indirect use or exclusion. For example, a lack of visual description, such as we find in the Hausa `Tale of Daudawar Batso’ (Ritchie, ch. 12 VSE), implies a corresponding lack of interest in (or repression of) the visual.

Finally, it is essential to consider the means by, and context in which. myths are passed on. Are they read in private or told to a group? If the latter, are they usually told in the dark or in the light? Are they told before meals, during meals, after meals? Are they danced? Sung? Represented in Pictures? What other sensors phenomena accompany their communication’? Are the myths understood differently by different groups within society?

9. Cosmology

– How are sensory data used to order the world? Are things classified by their colour, shape, smell, texture, sound, taste?

– What symbolic use is made of the imagery, of the senses?

– How are the ‘soul’ and ‘mind’ conceptualized? In which part of the body is the soul or mind thought to reside?

– What are the sensory characteristics of good or evil spirits?

– How are the senses elaborated in the afterlife? Is there a different sensory order from that of earthly life? Are sweet fragrances or good foods emphasized?Is there any sensory deprivation, such as darkness, silence, hunger?

It has often been noted that non-Western cultures classify things by sound to a much greater extent than do Western cultures (Ohnuki-Tierney 1981: Schieffelin 1976). Even more pronounced, at least in certain parts, is the classification of things by smell or taste. The Batek Negrito of peninsular Malaysia classify virtually everything in their environment by smell, including the sun and the moon. The sun is said to have a bad smell, `like that of rare meat,’ while the moon has a good smell, `like that of flowers’ (Endicott 1979: 39).

This is not so much a case of the `classificatory urge’ (Lévi-Strauss 1966) gone wild as an index of the centrality of smell in the Batek sensoriurn. This smell-mindedness also distinguishes the Batek as a people from the other people of the- Malay Peninsula (in a manner analogous to the way the differential extension of the senses by means of body decoration functions as a means of cultural differentiation in the Mato Grosso region of Brazil – see Seegher 1975). For example, the neighbouring Chewong also pay close attention to odours. However, unlike the Batek, they have only to be careful that no two different foodstuffs be present in the stomach at the same time (Howell 1984: 231). The Batek must never so much as cook meat from different species at the same time. for fear that the mixing of smells would offend the nostrils of the Thunder deity and bring calamity (Endicott 1979: 74). Thus, the order of both peoples’ universes depends on keeping the categories of creation separate; but whereas in the Batek case the distinctions are expressed primarily in terms of ethereal odours, in the Chewong case the categories are more substantive, having to do with stuffs. The greater substantivism of the Chewong cosmology is perhaps consistent with the heightened visualism of Chewong epistemology, as discussed by Howes in chapter 11 VSE.

in the previous section on myths, the importance of examining how a culture thinks ‘in’ or ‘through’ the senses was underlined. To grasp the indigenous epistemology it also helps to study how the culture conceptualizes and localizes the `soul’ or `mind’ within the body. Not all cultures are agreed in this regard. The ancient Greeks associated the soul with the breath, the Mehinaku of Brazil place the soul in the eye (Gregor 1985: 152), the Zinacanteco of Mexico, in the blood (Karasilc 1988: 5). In, the West, we think of the mind as residing in the head; the Uduk of the Sudan locate it in the stomach (James 1988: 69). According to the Aguaruna of the Amazon: `The people who say that we think with our heads are wrong because we think with our hearts. The heart is connected to the veins, which carry the thoughts in the blood through the entire body. The brain is only connected to the spinal column, isn’t it? So if we thought with our brains; we would only be able to move the thought as far as our anus?’ (Brown 1985: 19). What different sensory priorities and modes of thinking are produced by these different localizations of being and thought within the body?

A culture’s representations of spirits can be a good source of information on its sensory model. In cultures with a pronounced olfactory sensitivity, good spirits are often associated with good odours and evil spirits with bad odours (see Griffin, ch. 14). Care must be taken in analysing such material, however, for a one-to-one correspondence between the sensory profile of spiritual beings and the sensory order of human beings cannot be assumed. The fact that the chief deity of the Tarahumara of Mexico is blind, for instance, might lead one to think that the Tarahumara do not value sight. On the contrary, sight is of the utmost importance to the Tarahumara, since it enables them to provide the deity with game (which his blindness makes him unable to hunt for himself) and thus maintain a harmonious relationship between the supernatural and natural worlds (Kennedy 1978: 130).

The same caveat holds for the analysis of the rote of the senses in the afterlife. Sometimes the imagined sensory gratifications and/or deprivations of the afterlife replicate the ideal sensory model, at others they invert it, while in still other cases the afterlife is simply a projection of what a culture imagines the sensory existence of a corpse or– disembodied spirit to be. The Barasana of the Amazon, for instance, consider the world of the dead to be characterized by coldness, hardness, a strong odour, the separation of the sexes, and the consumption of `spiritual’ foods, such as coca, beer, and tobacco. To some degree this represents an ideal male sensory order, as men are supposed to be cold and hard. The complete realization of this sensory order, however, occurs only in the context of the male initiation rite. During this rite, initiates must. have no contact with fire or women, only tobacco, coca, and beer are consumed, and strong-smelling beeswax is burnt. During ordinary life, the ideal sensory order in fact consists of a combination of hot and cold, regular foods and spiritual foods. and so on (C. Hugh-Jones 1979, S. Hugh-Jones 1979).

It is of particular interest to examine representations of the afterlife in relation to the liturgy, or ritual life, of a given communitv. Sometimes it is possible to detect a sort of balance of opposites between the quality of worship and the vision of the afterlife. We think of the contrast between Islam, on the one hand, and Hinduism, on the other – Islam with its austere worship and sensual heaven, Hinduism with its sensual worship and ultimate transcendence or escape from sensation. Other religions appear to fall in-between these two extremes, such as some of the varieties of Christianity, where earthly liturgy and heavenly bliss mirror each other. Understanding the role of the senses in the afterlife postulated by a culture, therefore, requires first understanding the role of the afterlife in that culture.

Notes

1 The idea that human beings are equipped with five senses might seem obvious and beyond dispute, but it is in fact no less symbolic than other numerations. Acccording to the latest scientific estimates there are seventeen senses (see Rivlin and Gravelle 1984).

2 For a tasteful critique of the Mlackenzie Brown article see Pinard 1990. 3 How can one become aware of what one’s own sensory biases are? The simplest exercise for this purpose is the one initially popularized by Galton. The exercise involves recalling the scene at breakfast, describing it, and then analysing the extent to which you depend on each of your senses in memory. For example, is it the words for each of the objects on the table that come to you, or their visual images, or the motions you performed in grasping them, etc. The labels for these three pre-dispositions are ‘verbalizer,’ ‘visualizer,’ and ‘kinesthete’ (see James 1961: 169-77). More comprehensive discussions of how to discover your own sensing pattern, and how to control as well as use it for purposes of cultural analysis; can be found in Metraux (1953), Hall (1977: 169-87), and Cesara (1982: 48, 109-11).

3. Other techniques for enhancing sensory awareness include the ‘spiritual exercises’ first proposed by Loyola (see Synnott. eh. 5), and developed to an excessive degree by James Joyce (1946: 109-12). It is also helpful to consider the work of the musicologist R. Murray Schafer (1977) on ‘soundscapes’ and the geographer J. Douglas Porteus (1990) on ‘smellscapes’ and ‘bodyscapes’ by way, of sensitizing oneself to the limits of `the tourist perspective’ (Little, ch. 10), and coming to perceive how sounds, smells, and textures really matter in the environment of a given culture.

4. Like the Suya, however, the Dogon would seem to regard sight as an ‘antisocial’ or pre-social faculty. For example, it is by means of graphic symbols (paw marks) that Fox communicates with human beings in the context of Dogon divination. The dreams inspired in people by Fox are also silent. The reason for this is that Fox’s tongue was severed by the Creator. Amma, as punishment for resisting the latter’s cosmic plan and bringing death into the world (Calame-Griaule 1986: 102-3, 146).

5. In North American society, such skills are relatively underdeveloped, because of the paramount value attached to learning to read and write; which entails shutting up and sitting still. On the cognitive implications of the amount of stress different cultures attach to the development of different faculties, such as to read, to recite, or to dance, see Gardner (1983).

6 Indeed, why the fascination in Communications Studies departments with ‘the technologizing of the word’ (Ong 1982)?

7 While anthropologists normally search for ‘consonance’ across media (Douglas 1982b: 68), dissonances can be equally revealing. Stoller and Olkes (1990) have shown how messages in one medium, say the verbal message `This is a formal (read: "thick") social occasion,’ may be contradicted by those in another; for example, a woman serving a ‘thin’ (meatless, hence informal) sauce on the occasion in question (see further Appadurai 1981). Similarly, documentary producers have been known to get a point across by, for example, playing ‘Rule Britannia’ while images of London slums, as opposed to Buckingham Palace, pass by on the screen (Morgan and Welton 1986).

8 Of course, Western culture also employs non-audio-visual media of communication, such as food codes, but these are rarely explicit and are completely overshadow,ed by the dominant media.

9 One also wants to be attentive to hove the different environmental niches spanned by a culture (for example, sea and land) give rise to different sorts of sense perceptions (such as wet/dry, or feeling buoyant and moving speedily / feeling heavy and slow), and how these are valued and elaborated upon in the culture’s symbolic system, as Nancy Munn (1986) so well demonstrates in The Fame of Gawa

.

10 Perhaps the most splendid example of stimulating all the senses to the same extent at the same time is provided by the traditional Indian courts: ‘The fulfillment of every sense was considered an art in the Indian courts .. Scents were blended to suit moods and seasons and were believed to complement the colour of clothing’ – thus, musk was worn with winter silks; vetiver was associated with lemon scent, and gossamer went with summer garments’ (Patnaik 1985: 68). The complex combinatorics of emotions, seasons, and sensations played out daily in these courts has no western equivalent. Baudelaire’s Correspondances pales bb comparison (see Howes 1986: 42-3).

11 To illustrate, midway through the third stage of the trek, an informant told Daniel: ‘I stopped smelling things after Aruda Nati.’ To which Daniel responded: ‘Did you not even smell the camphor and incense sticks offered at the various shrines on the way after Aruda. His informant replied: ‘You might say I felt it. I didn’t smell it’ (Daniel 1984: 272). Incidentally, when the last of the senses, that of pain, `goes’ or `dissolves,’ close to the end of the trek; ‘love’ is said to take its place.

12 For an intriguing account of French thought in the sixteenth century, when the sensorium appears to have been more balanced, and `thoughts existed in a more clouded and less purified atmosphere’ than they have since the ‘Enlightenment,’ see Febvre (1982). According to Febvre (1982: 432): ‘The sixteenth century did not see first: it heard and smelled, it sniffed the air and caught sounds.’

13 Indeed, we are positively hindered from so doing by the glare of the television screen: ‘On the television screen, the world, broken down at its source, is reassembled as dots of light, and in this respect the television screen is everyone’s personal converter of light back into matter which originally has been decomposed as light.’ The television screen makes the world `matter as a matter of light;’ and that is all (Romanyshyn 1989: 186).

14 Of course, oral communication usually forms an important part of education in our society as well. It is not essential, however, as the existence of `correspondence courses’